Introduction of the Colldilocks Set

Lothar Collatz was a German mathematician born on the 6th of July, 1910. In 1937 he proposed a rather simple yet mind boggling problem that has since come to be known as the Collatz Conjecture. It is now recognized as a classic unsolved mathematical challenge, and a great enigma. The problem, also known as the 3x +1 problem is actually very easy to explain. It is the rather simple algorithm as follows:

Step 1: Start with any positive natural number.

Step 2: If the number is 1, stop.

Step 3: If the number is even, then divide it by 2, else it is odd, then multiply it by 3 and add 1.

Step 4: Go to step 2 with the resulting number.

It appears that, regardless of the starting number, the sequence of numbers produced by following these simple steps will always close on the following sequence: 16-8-4-2-1. More importantly, it will always lead to the value 1, which means according to step 2, we will always halt the sequence generation and more importantly, this will occur for all values of x. The problem and intriguing aspect of the conjecture is that since its inception, nobody has been able to prove that it is true for all cases of x regardless of how big we make it.

This is not to say that we haven’t tried. The current record for the count of numbers tested stands at 2 raised to the 68th power. For those less familiar with powers of 2, that would be 295,147,905,179,352,825,856. That’s a very large number, but even though all numbers in this range do lead to sequences that end in 1, it is not a proof for all values of x.

So let us take a walk with this problem by suggesting a comparison to the well-known children’s tale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. I will not repeat the story except to point out the introduction of the theme of too hot, too cold, and just right, and the need for a slight restatement of the problem.

The 3x +1 problem is a simple case of that class of mathematical expressions that we call a linear equation. And linear equations are rather important within mathematics. The 3x+1 equation is in a specific form that we call the slope-intercept form and generalize it to be:

y = mx + b

Where m is a constant that defines the slope of the line

b is a constant that reflects the y-intercept point of a plot on an XY graph

And x is the variable that y is dependent upon

So what is it about m = 3 and b = 1 that gives us this magical consistency in resolving all generated sequences to the value 1 when using this equation in the above 4 step algorithm? It is important to note that when m is not 3 and b is not 1, it is quite possible and actually more likely that you find some cycles will not ever stop at step two and generate a sequence of numbers for some values of x that go on for ever. And it is here that we make the connection to the children’s tale. Since for all values of x, you will produce a sequence of numbers. The exception case is when x is chosen to be 1 and you will end with a single value. Otherwise, in the terminology of the problem we produce a sequence of numbers ending in 1 that we call a cycle. Examples would be if we start with the number 3 then we would get the sequence:

3 -> 10 -> 5 -> 16 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

But the cycle lengths can be big. For instance if we chose to start with 27 we get:

27 -> 82 -> 41 -> 124 -> 62 -> 31 -> 94 -> 47 -> 142 -> 71 ->

214 -> 107 -> 322 -> 161 -> 484 -> 242 -> 121 -> 364 -> 182 ->

91 -> 274 -> 137 -> 412 -> 206 -> 103 -> 310 -> 155 -> 466 ->

233 -> 700 -> 350 -> 175 -> 526 -> 263 -> 790 -> 395 -> 1186 ->

593 -> 1780 -> 890 -> 445 -> 1336 -> 668 -> 334 -> 167 -> 502 ->

251 -> 754 -> 377 -> 1132 -> 566 -> 283 -> 850 -> 425 -> 1276 ->

638 -> 319 -> 958 -> 479 -> 1438 -> 719 -> 2158 -> 1079 ->

3238 -> 1619 -> 4858 -> 2429 -> 7288 -> 3644 -> 1822 -> 911 ->

2734 -> 1367 -> 4102 -> 2051 -> 6154 -> 3077 -> 9232 -> 4616 ->

2308 -> 1154 -> 577 -> 1732 -> 866 -> 433 -> 1300 -> 650 ->

325 -> 976 -> 488 -> 244 -> 122 -> 61 -> 184 -> 92 -> 46 -> 23 ->

70 -> 35 -> 106 -> 53 -> 160 -> 80 -> 40 -> 20 -> 10 -> 5 ->

16 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

In fact, we don’t seem to have a limit as to how big a cycle can be, we just guess that they will all eventually end at the value 1 for 3x + 1.

But we do know that if we try other values for m and b, we can get cycles that never end. And they will not end in one of two ways. They will either repeat a value that has already been encountered within the current cycle, in which case the sequence will repeat in an infinite loop. Or we will get an unlimited growth in the value of the result of the odd number cases. For instance, if we choose m = 3 and b = 2, it is probably very clear that the sequence will be infinite since for any odd number multiplied by 3 followed by the addition of 2 will always be odd.

3 -> 11 -> 35-> 107 -> 323 -> 971 … for ever in a 3x +2 expansion!

If we choose m = 3 and b = 3

This will be an infinite loop between step 2 and 3. And if we chose 3 for m and 3 for b we get:

1

2 -> 1

3 -> 12 -> 6 -> 3 -> 12 -> 6 -> 3 … for ever!

We also know that we can chose some values that result in behavior identical to the 3x + 1, which is to say that we will always generate a sequence that ends at the value 1 regardless of our chosen value for the variable x.

In the simplest case take the value 0 for m and 1 for b. We get the following sequences:

1

2 -> 1

3 -> 1

4 -> 2 -> 1

5 -> 1

6 -> 3 -> 1

7 -> 1

8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

9 -> 1

10 -> 5 -> 1

And so on. In this case we can prove that the sequence will always end at the value 1 since, if x is even, we keep dividing it by 2 until it is either odd or 1. And if x is odd, it will always become 1 since (0 * x) + 1 will always equal 1 regardless of the value of x.

If we chose 2 for m and 2 for b we get:

1

2 -> 1

3 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

4 -> 2 -> 1

5 -> 12 -> 6 -> 3 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

6 -> 3 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

7 -> 16 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

9 -> 20 -> 10 -> 5 -> 12 -> 6 -> 3 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

10 -> 5 -> 12 -> 6 -> 3 -> 8 -> 4 -> 2 -> 1

In fact there are an infinite number of Collatz Conjecture like number pairs for (m, b) that will behave as the 3x + 1 problem. Most values for any arbitrary chosen pairs will result in infinite sequences by either looping on a repeating sequence (too cold) or an infinite expansions of ever increasing calculations on odd numbers (too hot).

But it turns out that some pairs are just right and result in all sequences for any given value for n will converge on the value 1. The only variables are the lengths of the cycle, the convergent values between two different sequences, and the point of convergence onto the closing sequence of powers of 2 that ultimately resolve to 1.

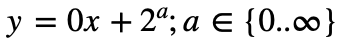

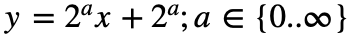

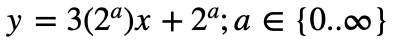

The existence of this set of number pairs that behave the same as the 3x + 1 problem with all sequences generated for all values of n that converge on 1 will be called the Colldilocks set. The Colldilocks set can be calculated by the union of the sets of the m and b pairs of the following 3 formulas:

And

And

This would be: {(0,1), (0,2), (0,4), (0,8) … } + {(1,1), (2,2), (4,4), (8,8) …} + {(3,1), (6,2), (12, 4), (24,8) …}

All m,b pairs will always have some values of n that will be just right and resolve to one. The choice of any power of 2 will never exit the even expression and will always resolve to one by constant division by 2. Some m,b pairs may have some values of n that also resolve to 1. However, any m,b pair outside the Colldilocks set will fail with at least some cycles generated for some values of n that will be too hot or too cold leading to the following conjecture:

Conjecture: All (m,b) pairs within the Colldilocks set will generate cycles that resolve to 1 for all values of x. All (m,b) pairs that are not in the Colldilocks set will result in some values of x that produce cycles that will be either too hot or too cold with the possibility that some non power of two values for x will produce cycles that will resolve to 1.

Con l’algoritmo di Collatz non è possibile elaborare tutti i numeri naturali perché non conosciamo: quantità e valori dei numeri pari e dispari e tutti i loro fattori. Dal triangolo di Tartaglia possiamo rilevare i numeri dispari che sono la somma dei risultati delle infinite potenze di 2 che hanno indice pari e che sono anche uguali al precedente dispari * 4 + 1. Questi sono tutti i numeri dispari che * 3 + 1 genera un numero pari che è il risultato di una potenza base 2 e indice pari 2 ^ (2 * n≥1) e che, l’ennesima metà, finisce in 1 perché ½ di 2 ^ 1 = 2 ^ 0 = 1. https://vixra.org/abs/2112.0004

English Translation: With the Collatz algorithm it is not possible to process all natural numbers because we do not know: quantities and values of even and odd numbers and all their factors. From Tartaglia’s triangle we can detect the odd numbers which are the sum of the results of the infinite powers of 2 which have an even index and which are also equal to the previous odd * 4 + 1. These are all the odd numbers which * 3 + 1 generates a even number which is the result of a base power 2 and even index 2 ^ (2 * n≥1) and which, the nth half, ends in 1 because ½ of 2 ^ 1 = 2 ^ 0 = 1

Pingback: The Collatz Calculator | SophWares